The question I get asked more than anything else, from people out in blog-land and from people in real life, is why we home school and how we came to that decision, and to be honest I’ve been asking myself that question a lot since Hunter was born. Adjusting to life with a newborn, whether it’s the first or fifth, is hard and magical and tiring and exhilarating and emotional and… Well, there have been many times during the past 2 months that I wished everyone would just go away, that the free daycare that is public school has sounded totally worth it.

So, I’m going to take this week to spend some time answering that question and reminding myself at the same time why it is I’ve chosen this crazy ride. Hopefully this will be helpful to someone out there. If nothing else, it will be helpful for me. It’s always good to revisit things.

I’m just going to write what flows today and we’ll see where that leads…

When I graduated from high school I didn’t feel very “educated.” I just felt like there was something missing– that I hadn’t really internalized much real knowledge or fully developed my talents. I graduated with good grades, did well on my AP English and Art exams, had a decent ACT score, but all that good paper seemed empty. I knew that I could count on one hand the books I had actually read, even though I had written lots of good papers about books I merely payed attention to discussions of. I knew that more of the time I spent in the art studio was wasted on listening to music and goofing off with my friends than it was getting an understanding of what art is and the art I was meant to make and then actually making it. I didn’t remember much from my science classes, even the ones where I had gotten the highest scores on the final exams. I knew that for all my thirteen years the thing I had most internalized was how to play the game, how to get teachers to like me and tell me I was smart by giving me good marks. I also knew that as a result, my sense of self worth was largely based on what others thought of me and the attention and recognition I could get for the things I did do. I did have a few classes that gave me a vision of what real learning could be. I fell in love with the scriptures during my LDS Seminary classes. I learned how to identify universal principles that could be a guiding force in my life and then test them by actually applying those principles in everyday living and making those principles an integrated part of my being. My AP English class my senior year was life changing. I found my voice in writing, found a community of friends that could really think about things and discuss them, and learned that learning comes from reading, pondering, discussing, and then producing something in response to really make the knowledge mine– to make it a part of me. For Honors American Government we dressed in professional clothes and went daily to the state capital to sit in on committee hearings, watch debates on the floors of the House and Senate, write articles about what was happening there, conduct mock floor debates to see and feel like a part of real things happening that affectedreal people’s real lives. But, apart from seminary, these experiences happened the very last year of my public schooling, and I was one of the lucky ones. It was a small minority of students that had experiences like I did.

I went to college expecting that those classes my last year of high school were just a glimpse of what college would be like, that inspiring learning would be waiting for me at every turn. For the most part, though, it was a return to playing the game as usual– figuring out how to regurgitate information just the way the teacher wanted it. I did learn how to learn in college, though. There were a handful of classes that I got that from, but my best teacher was the enormous library within walking distance of where I lived. My deepest learning came from reading everything I could about a topic I was interested in, trying to do it or apply a principle in my life, read some more, do some more… I learned to knit, bind books, to tell the difference between art work by Fra Angelico and his students, about identifying birds and trees. I realized that no one else but me was responsible for my learning. Teachers and professors could ask questions, suggest angles from which to see something, prescribe reading and writing, but when I actually learned something it was because I was intensely interested in it, spent a lot of time reading and dreaming about it, and wrote or made something in response.

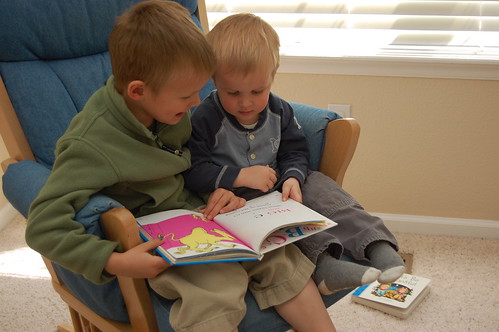

And over the course of these years of really wanting to feel like I was getting an education, learning and knowing things, I was also in the middle of dreaming up what I wanted my future family to be like, and actually getting married and starting that family. I kept asking myself, “Why does school have to feel like so much wasted time with little jewels of inspiration, light, and knowledge sprinkled in? Could it be the other way around? Could the process of getting an education be FULL of inspiration, growth, real internalized learning with maybe a little monotony sprinkled in instead?” If it was possible, that was the kind of experience I wanted for my future children. I wanted to create a family culture of wonder and appreciation for nature, each person’s unique talents and abilities, and that anyone could learn and gain mastery about anything they studied, applied and tried.

Then a friend introduced me to the ideas in A Thomas Jefferson Education by Oliver DeMille.

She told me the seven principles of facilitating a good education are:

Classics not Textbooks

Even though it is hard work to study original sources, it is best to know what Darwin or Aristotle or Dickens actually said, than what someone said someone said Darwin or Aristotle or Dickens said. A classic is any work that you can return to over and over again and keep learning from. Books can be classics, works of art, music, nature… original works that bring us face to face with the greatest the world has to offer.

Mentors not Professors

A professor lectures and tests—mostly from his own point of view.

A mentor works with a student, giving suggestions, asking hard questions, helping the student set goals, and holding them accountable for what they say.

Quality not Conformity

Mentors only accept excellence. They help guide students to reach their unique potential, not just beaurocratic standards.

Structure Time not Content

School needs to be held at a set time everyday. (suggested 3 hours/day) Kids choose what they study. Remember all truth is intertwined—and kids don’t compartmentalize the way adults do. They will learn a diversity of subjects, even if they choose to study motorcycles for weeks! Be creative in helping them, and they’ll learn everything they need to and more.

Inspire not Require

Great teachers set the example and show their excitement about learning. They ask themselves, “What can I do to get my children to WANT to read or do math etc. etc.?” They pray hard and work hard because children do what they see modeled.

Simplicity not Complexity

As curriculums get more and more complex, children learn less and less.

Great education occurs when students study.

Students study when they choose to.

Students choose to study when they’re inspired.

And then I knew I wasn’t the only one feeling something missing from my educational experience and I needed to set out to do something different with the children that would come into my family.